Obese Dachshunds Understanding the Health Implications

Understanding Health Policy to Improve Primary Care Management of Obesity

Obesity management for most primary care providers (PCPs) is difficult especially in this obesogenic climate. However, PCPs especially nurse practitioners (NPs) are ideal candidates for making overall positive health changes for obese patients. PCPs can vote, have medical expertise, and are poised to promote obesity reduction by: 1) influencing patients/ families to make healthier lifestyle choices, 2) providing patients with individualized, evidence-based health information, 3) encouraging healthcare systems/ workplaces to provide healthy environments for all stakeholders, and 4) advocating for local, state and national healthcare policy changes. The purposes of this paper are to increase PCPs awareness of health policys influence on achieving best management practices for obesity management and the clinical implications of caring for this population.

Obesity

Adult obesity is a body mass index (BMI) 30 kg/m2 and in children and adolescences, a BMI the 95th percentile for the same age and sex. Obesity is multifactorial, encompassing genetic, physical, environmental and psychological components and obesity transcends regions, races, and genders 1. Obesity affects approximately 17.0% (12.7 million) of children ages 219 and 35.7% (80 million) of adults 2,3. Obesity prevalence is higher among adults ages 4059 years old (39.5%) followed by adults 60 and over (35.4%), and then younger adults between the ages of 2039 (30.3%) 1. Obesity is a global disease with many costly, chronic co-morbid conditions including type 2 diabetes, hypertension, gallbladder disease, osteoarthritis, dyslipidemia, coronary heart disease, and some cancers 4. Obese persons currently have improved access to obesity management and PCPs have more reimbursement options 5,6. Unfortunately, continuation of coverage for this costly disease is now uncertain.

Cost of obesity

Obesity is associated with increases in healthcare costs and thus has a negative influence on the economy. For example, roughly 34.4% of uninsured adults who are eligible for Medicaid are obese and require healthcare interventions 7. The probable annual impact of obesity on the global economy is $2 trillion dollars, which accounts for 2.8% of the global gross domestic product 8. The oldest baby boomers reached the age of 65 in 2011. Healthcare expenses of this large cohort, which is expected to live longer than previous generations, accounts for 66% of Americas healthcare budget 9. If current obesity trends continue, approximately half of adults, including those over age 65, will be obese by 2030 8. Medicare and Medicaid cover roughly 40.0% of the annual obesityrelated healthcare costs ($60 billion) and current investigations suggest that a 5% reduction in the obesity rate would yield a healthcare savings of approximately $29 billion 3. Likewise, the annual medical costs associated with childhood obesity among 8 to 13 year olds and 14 to 19 are $240 and $320 respectively per child. However, if no incremental, lifetime adjustments for medical cost are made for normal weight children, who may potentially gain weight during adulthood, the estimated costs for obesity treatment will range $16,310 to $39,080 per person 1012. The financial implications of reducing obesity prevalence are huge. Therefore, addressing barriers to obesity reduction with a multidimensional approach, which encompasses environmental factors, is essential.

Obesogenic environment

The concept of the obesogenic environment first emerged in the 1990s 13,14. The obesogenic environment is a group of diverse communitys features that increases peoples risk for obesity and its related complications 13. Research suggests a link between obesity and built environments where people live, work, and play 1517. The built environment can negatively affect physical activity and health outcomes. For example, a healthy built environment is a neighborhood with good aesthetics (e.g., more green space), sidewalks, safe traffic conditions, and convenient full service grocery stores. This environment facilitates healthy lifestyle behaviors 18 needed to reduce obesity 17. Understanding the possible association of sedentary and unhealthful eating behaviors with the built environment provides a framework for developing strategies aimed at reducing or eliminating the obesogenic environment.

Equally important are other external factors in the built environment 19. Research proposes that walking is the primary mode of exercise for adults 20 and active free-play for children 21. Walkability (e.g., sidewalks, parks or recreation centers) and playability (e.g., yards, playgrounds) of a neighborhood are associated with physical activity in adults and children respectively 22,23. Environments that are not conducive to physical activity may increase the risk of obesity. Hence, the need exist for healthcare policies based on science and the values of the population to create built environments that promote an active lifestyle in all communities, and thus eliminate or reduce obesogenic environments.

Research also suggests that African Americans and low-income people are more likely to live in obesogenic environments with limited access to neighborhood supermarkets and healthy food choices than European Americans 24. More recently, Lee et al 25 reported findings from a qualitative study of 34 obese minorities that reveal perceived discrepancies between cost of healthy and unhealthy foods in their neighborhood supermarkets. These findings emphasize the perceived or actual barriers faced by vulnerable populations to achieve healthy eating behaviors.

Policy influence on obesity healthcare

Health policy is an official statement or process that summaries priorities and restrictions for actions that address health needs, identifies available resources, and responds to a systemic process or administrative pressures 26,27. Specifically, health policy is needed to establish a consensus and to outline transparent, future direction of health outcomes for health systems, PCPs, and the general public 27. Policies may help create strategies and built environments that promote healthy lifestyles and prevent obesity. For example, PCPs, especially pediatricians, have a unique and important role in promoting policy change and environments that support obesity reduction 28 because early childhood is a crucial time for healthy lifestyle development 29. During the first two years of life, PCPs have multiple opportunities during well child visits to educate parents about maintaining healthy lifestyle behaviors and referring families to community resources 29 to aid in obesity reduction.

To ensure that healthcare outcomes and policies related to obesity are applicable, PCPs and scientists from appropriate disciplines must evaluate current obesity research findings along with expert position papers from groups like the ADA 30 and the National Academy of Medicine 31. Because of the national urgency to provide preventive and proactive healthcare to persons diagnosed with obesity 32, PCPs need to be present in all levels of governmental (decision-making) committees associated with redesigning obesity healthcare and policy development 33. Moreover, PCPs expertise complements that of policy makers who rarely have the medical experience necessary to develop policies that address current obesity health issues. Specifically, PCPs are poised to fill in the gap to advocate for health policy changes to help vulnerable populations and to suggest appropriate changes in the delivery of healthcare 33 for obese patients.

Obesity Guidelines

New and revised clinical practice guidelines based on evolving science are a promising approach to encourage and advocate for health policy changes 34,35. Currently, published clinical practice guidelines identify obesity, metabolic syndrome, diabetes and heart disease as chronic inter-related conditions 36. Prevention of these chronic diseases must encompass ongoing assessment of the patients BMI, waist circumference, and willingness to adhere to healthier lifestyles behaviors. Research consistently suggests that prevention of these problems should begin with early childhood screening and promotion of a healthy lifestyle 37 by PCPs.

With decreasing numbers of PCPs and increasing numbers of newly insured obese patients (because of the affordable care act), the demand on PCPs to manage these patients will be overwhelming 38. However, if all PCPs use clinical guidelines to manage and treat obesity, the continuity of care for this patient population may improve, which may led to reductions in obesity prevalence. For example, clinical guidelines should include therapeutic conversations with obese patients regarding healthier lifestyles to reduce obesogenic environmental influences 39 and when to refer these patients to obesity specialist, especially when patients health outcomes have moved beyond the NPs scope of practice and education 40.

PCPs influence on obesity healthcare policy

PCPs recognize the priorities and issues that accompany treating obese and overweight individuals, such as sufficient time for educating and counseling patients. PCPs need a minimum of 2030 minutes to spend with obese patients especially those with multiple co-morbidities 41 instead of the usual 1015 minutes for an office visit. In other words, practice guidelines suggest specific interventions for this population require more time - even for follow up visits 42. However, the provider must comprehensively document the visit based on the insurers reimbursement standards in order receive payment. Clinical decisions made outside of the group norms or the values of the employer/agency usually lead to denials for reimbursement. As a result, primary prevention is often no more than a caution that overweight and obesity are present and the individual should get more exercise and watch their diet. This is seldom effective without specificity. Specialty clinics are available for some and referrals are common, but often not until serious co-morbidities have developed. Specialty providers, in turn, are frustrated that PCPs do not intervene earlier or the treatment was not effective or properly administered 32.

This complex situation requires the PCP to recognize that existing health policy may be a contributing factor, whether the policy is that of the state, the nation, the employer, or the agency or institution. PCPs must be advocates for their patients, highlighting the barriers to individually appropriate care. In the community, PCP and professional organizations can help identify common problems and organize support for providing quality health services and a safe environment for all people. PCPs and organizations can seek support and assistance from governmental policy makers and legislators, to influence policy development at local, state, and national levels, and to pursue appointments to committees and elections to public office that may offer opportunities to change policies.

Clinical goals for obesity management

One of the Healthy People 2020 objectives (Nutrition and Weight Status: NWS-5 ) is to increase the percentage of PCPs who evaluate their patients BMI level on every visit 43. PCPs are essential in monitoring the health of patients and a primary strategy to achieve this goal is the use of screening. In 2011, Medicare announced a coverage decision describing the criteria for intensive behavioral counseling and therapy for beneficiaries classified as obese 44. Furthermore, primary care experts recommend offering and referring all obese patients for obesity treatment interventions that include setting weight-loss reduction and self-monitoring goals, assessing facilitators and barriers to change, and planning how to achieve and maintain lifestyle changes (e.g., increased physical activity, healthier diet) 42.

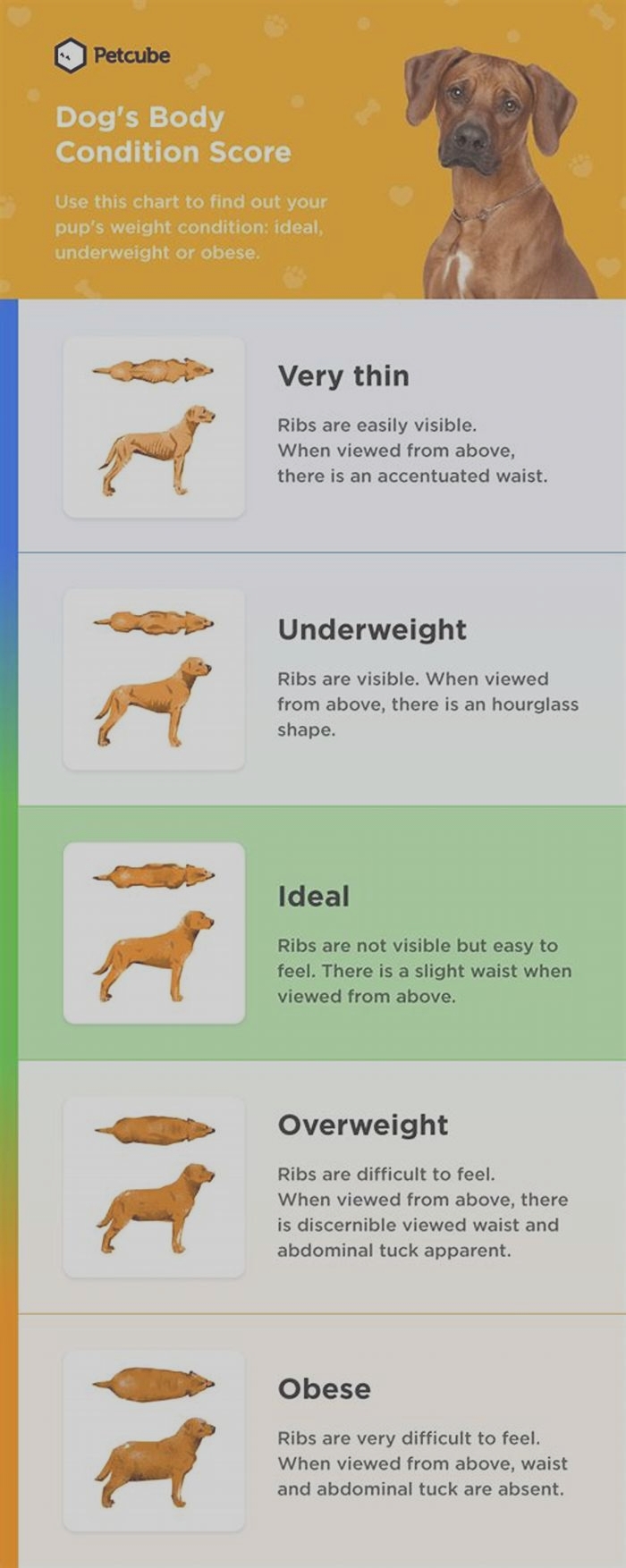

Unfortunately, many inconsistencies in healthcare plans exist related to the amount of primary care coverage provided for obesity treatment 45. Research suggests that obese children are more likely to become obese adults. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends that PCPs screen children 6 years and older for obesity and offer them thorough behavioral strategies to promote a healthy weight. Furthermore, adults, like children who are overweight/ obese, should be referred for multidimensional, behavioral programs that include nutritional and physical lifestyle behavioral counseling that is more likely to result in weight reduction 46. However, for screening to be effective, all PCPs should follow a standard protocol to ensure continuity of care for all overweight and obese patients. See as an example.

Table 1.

Clinical Protocol for Obesity Management a,b,c

| ProceduralSteps | Actions to take | Sub-actions |

|---|---|---|

| Subjective: | Assess: Past medical history Family History for obesity Patients Review of Systems | Assess readiness for change & motivation level, self-awareness of obesity status, and current activity level |

| Objective: | Evaluate: 1) Degree of obesity 2) Health risk status | Vital signs, complete physical exam, height, weight, BMI, & waist circumference.Labs: CMP, TSH, CHO panel, HgbA1c. Presence of comorbidities (e.g. CHD, hypertension, Type 2 diabetes, Sleep Apnea) |

| Treatment: | ||

| Step 1 | Determine and contractmutual goals with patient | Prevent further weight gain, reduce body weight,maintain weight loss |

| Step 2 | Develop SMART goals with patient | For success, goals must be: Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Realistic, and Timely |

| Step 3 | Generate lifestyle strategies to achieve SMART goals | Create charts with specific goals/ timelines for mental, physical activity, and nutritional behaviors |

| Step 4 | Provide assistance to achieve goals | Make referrals to dietitians, exercise trainers, counselors, psychologists, pulmonologist as needed. Provide self-management tools such as websites that help manage/ track food intake and activity level. Order activity tracking devices e.g. Fitbit |

| Step 5 | Frequent follow-up | Schedule follow-up every 23 months for reevaluation of facilitators and barriers and adjustments as needed |

| Step 6 | Consider pharmacotherapy | Use short-term as adjunct therapy to improve nutrition and physical activity lifestyle changes |

| Step 7 | Explore bariatric surgery | Recommend this option for morbidly obese patients who have several comorbidities and have been repeatedly unsuccessful with weight loss attempts |

Health policy implications

Recommendations from the USPSTF encourage PCPs to provide intensive, multidimensional behavioral strategies to all obese patients 45. Strategies include behavioral management activities such as: a) identifying weight-loss goals, b) improving diet or nutrition, c) increasing physical activity, d) addressing barriers to change, e) self-monitoring/sustainability of lifestyle change, and f) participating in weight-loss interventions that includes 12 26 sessions a year and provide a variety of activities and approaches to aid in successful weight reduction 45.

Policies which address obesogenic environmental factors that impact a patients quality of life and health outcomes 50 are needed. For example, an individual with limited access to safe housing compared to his counterpart living in a nice, comfortable home within a safe community may have poorer quality of life, which can directly affect health status 51. Specifically, PCPs are cognizant of the effects of socioeconomic status on ones health and adept in educating patients, peers, and policy makers on the effects of social inequalities among vulnerable populations 52. Therefore, PCPs are equipped to encourage, persuade, and petition for policy changes to reduce obesogenic environments, which may subsequently led to reductions in obesity rates.

PCPs can advocate for policies that would support obesity prevention across the lifespan, such as more activity and healthier food options in schools and in the workplace. Specifically, policies that focus on providing access to healthy, affordable food and more safe spaces to promote physical activity 28 in all communities. Another example of how PCPs can influence policy is to engage insurance companies. Insurer policies frequently do not cover obesity or counseling for overweight or obese clients beyond their annual well visit. The Affordable Health Care Act (ACA), if not appealed or underfunded, provides added support for annual visits. PCPs can advocate for better policies to fund such activities as gym subscriptions for patients or rewards for weight loss and other health outcome goals. Prior to the ACA, preventive screening and education were either not covered or inadequately covered to compensate for the extensive counseling required. Insurers mainly covered treatment for morbid obesity with other co-morbid conditions, which included surgery in some cases, while overweight or moderately obese patients were encouraged to exercise & eat less. Thus, PCP are positioned to advocate for legislative, professional organizations, and insurance companies to focus on policies that relieve or remove major healthcare barriers to managing obesity. Specifically, emphasis should focus on obesity prevention and access to obesity healthcare for all people who are at risk 47,48,53. Unfortunately, the challenges for the adoption of healthier lifestyles 29 for all people are great. However, encouraging more PCPs to become politically active may be an underused strategy to reduce obesity prevalence through policy.

Systematic reviews of evidence are particularly useful in evaluating existing health policies and health outcomes. For example, a systematic review of obesity-related policy and environmental interventions were published for consideration of economic outcomes 54. Such documents provide a template for PCPs to promote health policies that address the difficulties associated with obesity, metabolic syndrome and other co-morbidities among individuals, communities, states, and the nation.

An example of how PCPs can translate research into practice is the use of the WellRx Toolkit 55, which is an 11-item self-report screening instrument that allows PCPs to identify and address social needs experienced by community-dwelling patients. Researchers used this instrument to screen over 3,000 patients from three primary care sites. Findings revealed that 46% of patients screened positive for at least one social need and 63% of those had multiple needs. If PCPs use this toolkit among their patients, addressing social barriers may improve overall patient healthcare outcomes. Another approach PCPs may use is lay people or community partners such as Community Health Workers (CHW) to assess peers for barriers to chronic care management such as obesity treatment. CHWs have a unique set of skills that help patients navigate the healthcare-systematic processes.55 For example, a CHW can assist a patient with filling-out paperwork for subsidies related to a diagnosed chronic disease. These strategies demonstrate how PCPs can educate and inform community partners and policy makers about barriers to healthy living in addition to facilitating policy changes that may improve obesity-related health outcomes.

Conclusion

Ultimately, this paper highlights the need for PCPs to become politically active at all governmental levels in order to improve obesity management and treatment by reducing the influence of obesogenic environments. In addition, it highlights unique strategies for integrating obesity-research findings in the primary care setting that could translate into decreased obesity prevalence. Future studies that examine relationships between the obesogenic environment, health policy, health outcomes, and obesity may inform policy-decision makers of needed changes in healthcare policies at all levels of government and researchers to be cognizant of the obesogenic environment when developing tailored interventions for vulnerable populations across the lifespan.

Contributor Information

Pamela G. Bowen, Acute, Chronic and Continuing Care Department, School of Nursing, UAB | The University of Alabama at Birmingham, NB 416 | Mailing address: 1720 2nd Avenue South | Birmingham, AL 35294-1210, P: 205.934.2778 | F: 205.996.7183 | ude.bau@newobp.

Loretta T. Lee, Acute, Chronic and Continuing Care Department, School of Nursing, UAB | The University of Alabama at Birmingham, NB 542 | Mailing address: 1720 2nd Avenue South | Birmingham, AL 35294-1210, P: 205.996.5826 | F: 205.996.9165.

Gina M. McCaskill, UAB School of Medicine, Division of Gerontology, Geriatrics, and Palliative Care, P: 205.393.5888.

Pamela H. Bryant, Family/Community and Health Systems, School of Nursing, UAB | The University of Alabama at Birmingham, NB 428D | 1720 2ND AVE S | Birmingham, AL 35294-1210, P: 205.934-2640 | F: 205.996.7183.

M. Annette Hess, Nursing Graduate Programs, School of Nursing Office 1515 A, P: 205-726-2708 | F: 205-726-2219.

Jean B. Ivey, Family/Community and Health Systems Department, School of Nursing, UAB | The University of Alabama at Birmingham.