Bulldog Obesity The Benefits of Agility Training for Weight Loss

Fat Bulldog: How To Deal With Bulldog Obesity

Do you have a fat Bulldog? Nearly half of the dogs in the United States are overweight. Unfortunately, Bulldogs are one of the breeds that are prone to obesity. Other breeds that are prone to gaining weight include Dachshunds, Labrador Retrievers, Boxers, Basset Hounds, and Pugs.

Obesity is especially detrimental forbrachycephalicdogs, such asPugs and Bulldogs. The structure of their skeletons and faces already makes it difficult for these dogs to breathe. Excess fat deposits in the chest and airways can further restrict their breathing. This can make them prone to respiratory diseases, includingbronchitis.

If you have a fat Bulldog or one that is gaining a few extra layers of skin rolls, here area fewthings you must know.

Signs Your Bulldog is Obese

To find out whetheryourBulldog is obese, check for the following signs.

Thebody of a fat Bulldog has no defined shape

Bulldogs are naturally thick, stocky,and roundish to squarish in shape. For this reason, it can be difficult to determine whether your Bulldog is in goodshape or not. However, dogsshould have waists that are slightly slimmer than their hips. If your Bulldoglooks like a chunky sausage, then he is definitely fat.

Afat Bulldog is often unable to scratch his own body

A fat Bulldog tends to have rolls of fat deposits in his body. These fatty layers can inhibit your pet from scratching or licking some parts of his body. Your Bulldog may not be able to scratch his ear using his back paws or any of his paws. He may also have a hard time scratching some parts of his body that he normally scratches using his teeth.

Breathing is even harder for a fat Bulldog

As a breed, Bulldogs have the tendency to snort and pant a lot. But if a Bulldog is fat, his airways tend to get narrower and saggier.

Causes of Bulldog Obesity

Bulldogs are notorious eaters,and they can be very greedyforfood. On the other hand, Bulldogs are not known for theirlovefor exercise. The imbalance between diet and lack of sufficient exercise is the main cause of obesity in Bulldogs. High-calorie food and frequent treats also contribute to their weight gain.

Hypothyroidism and neutering can also cause obesity in Bulldogs.

Bad Health Effects: A Fat Bulldog is prone to many diseases

Like an obese human being, a fat Bulldog is prone to the following health issues.

- Increased risk of heat stroke

- Exercise intolerance

- High-blood pressure

- Diabetes

- Liver disease

- Some forms of cancer

- Osteoarthritis

- Increased risk of hip dysplasia

How to Deal with Bulldog Obesity

It can be difficult to make a fat Bulldog lose a few pounds. Because of their physical shape, forcing Bulldogs for hard and long exercises is strongly discouraged. But here are a few things you can do to help your fat Bulldog become fitter.

- Check your Bulldogs weight.Ideally, a male Bulldog should weigh between 50 to 55 lbs while female Bulldog should be around 47 to 50 lbs.

- Alter your Bulldogs diet.Look for high-quality but low-calorie dog food for your pet. Feed your Bulldog small meals throughout the day instead of giving him two full meals per day.

- Choose ahealthy dog treat.Instead of getting treats from a pet store, try giving your fat Bulldog sliced cucumbers, apples (without the pit), broccoli, celery, green beans, or bananas. Make sure to only give a fat Bulldog a treat after you ask him to do something to earn it.

- Rule out hypothyroidism and other possible health issues.When a dog has hypothyroidism, his thyroid gland fails to produce adequate levels of thyroxine, which is the hormone responsible for converting food to fuel (energy). Without enough thyroxine, your Bulldogs body is unable to use the food he consumed for his daily activities. If your Bulldog shows signs of hypothyroidism or any health issue, consider taking him to a veterinarian.

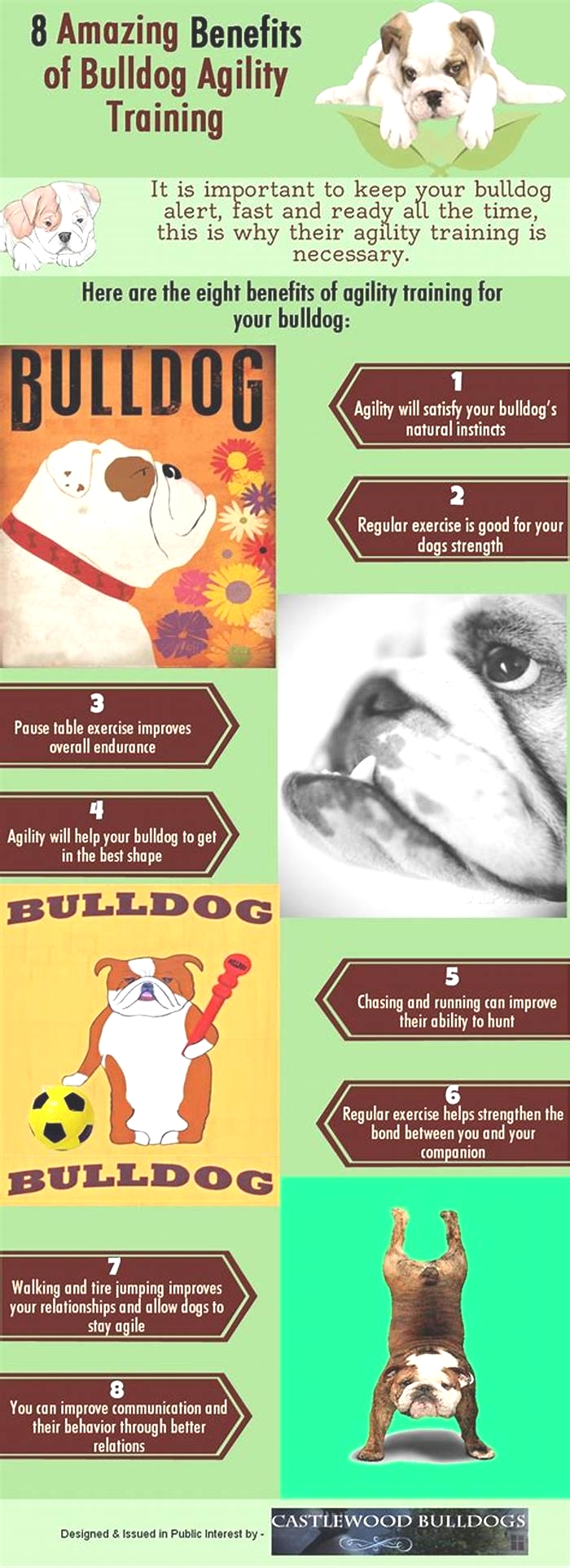

- Exercise your Bulldog.Strenuous exercises are not suitable for Bulldogs,especially fat ones,as they get tired easily and are prone to heat stroke. But there are a few Bulldog exercises yourpet do. Just make sure not to let your pet overdo them.

Leave a Reply:

Leave a comment below and share your thoughts.

Why dancing may be better for weight loss than other forms of exercise

- Dancing offers a valid way to exercise, and, as it is so much fun, it may be easier to keep at it long-term.

- A new meta-analysis assessed evidence collected in 10 studies that considered the health benefits of various types of dance for people with overweight and obesity.

- Dance arguably provides more entertainment than traditional exercise while it improves mood and executive function, and provides a chance to enjoy more social interaction.

Exercise, while it is recommended for weight loss, can be difficult to maintain over the long term. It is often repetitive and monotonous, frequently hard, and often solitary.

Some researchers have found, however, that dancing can be an effective way to lose weight. As a physical activity, dancing is typically more fun than conventional exercise, and can even provide a venue for social interaction.

A recent meta-analysis that assessed the evidence brought forth by 10 studies investigating the benefits of dance for people with overweight and obesity has drawn this conclusion.

The analysis found that people who regularly engaged in dance exhibited improvements in body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, percentage of body fat, and kilograms of fat lost compared to people who did not dance.

The paper appears in

In the studies, numerous dance forms were included, including step-aerobic dance, cheerleading, creative dance, Zumba, bhangra dance, traditional dance, dance video games, square dance, simplified dance, and aerobic fitness dance.

With the exception of square dancers, who danced for 5 days each week, and bhangra dancers, who danced twice a week, all other study participants had three dance sessions weekly.

Dance sessions ranged from 40 minutes to 90 minutes. All of the studies lasted at least 4 weeks, most lasted for 3 months, and one lasted for a year.

The key to any successful exercise program is adhering to it past the initial decision to get started, and dancing may offer enough entertainment value to make this more likely.

As Dr. Jagdish Khubchandani, professor of public health at New Mexico State University, not involved in this meta-analysis, noted to Medical News Today, [t]raditional exercises require a lot of motivation and are perceived as an effort, often with high demand, [for instance] economic, physical [concerns due to] pain, time, etc.

Stephanie Escobedo, founder of Through the Body, a dance and fitness company, also not involved in this research, told MNT that finding a type of exercise that you enjoy will make it easier to commit to doing the physical activity on a regular basis.

Dr. Menka Gupta, functional medicine doctor at NutraNourish, commented on the findings of the meta-analysis, noting that it is not the first to come to the conclusion that dancing provides health benefits.

She noted that dance provides enough pleasure to warrant consideration as a strong exercise option for people interested in improving their physiological health.

Dr. Gupta also pointed out that dancing may offer additional benefits beyond improving ones BMI. Enjoyable physical activity can also boost mood and reduce stress, providing additional mental health benefits of exercise, she told us.

Pleasure is also a good motivator, as pleasure is linked to dopamine. Enjoyable physical activity also seems to promote better sleep, providing additional health benefits, added Dr. Gupta.

Dr. Khubchandani further cited a

But what is the best form of dance for people seeking to improve their health?

Dr. Gupta put it simply: When people ask me about the best form of exercise, my usual response is, something you enjoy so that you will stick with it over the long term and be consistent with it.

Dr. Khubchandani had a similar point of view, adding that one should choose a financially affordable dance form that you can engage in consistently, helps you build a routine and social relationships, and is preferably high-intensity (e.g., hip-hop, Zumba, etc.).

Dr. Gupta suggested ballroom dancing as a great option for older individuals, or for those seeking something with lower intensity: It is great for social interaction and helps develop a feeling of community. It is also great for improving balance, posture and cardiovascular health.

She also endorsed Zumba, which typically incorporates interval training alternating fast and slow rhythms. It is, Dr. Gupta said, a form of high-intensity interval training that can also help a person stay sharp mentally.

[Zumba] also improves mood and cognitive skills such as decision-making. It helps develop new neural connections, especially in regions involved in executive function, long-term memory, and spatial recognition.

Dr. Menka Gupta

As a bonus, she said, Zumba helps reduce stress, and increases levels of the feel-good hormone serotonin.

Escobedo said she believe[d] that all forms of dance are beneficial to health.

Ballet, she suggested, is a great way to work on muscle strength, balance, posture and cardio endurance.

Modern/Contemporary dance is another style that is beneficial for similar reasons to ballet, but contemporary dance has dancers getting up and down from the floor, which builds better agility and core strength, added Escobedo.

She also noted that the most popular dance class, in her experience as an instructor, is a cardio dance class that promotes weight loss, cardio endurance, balance, agility, coordination, memory and so much more.

Class members get from 3,000 to 5,000 steps in one 50-minute session.

It feels more fun than a chore like physical activity can sometimes feel, suggested Escobedo.

Dr. Gupta mentioned one other consideration when settling on a dance: Choosing one that resonates emotionally with you and those you will be dancing with.

In her case: My personal favorites are Zumba and Bollywood dancing. Bollywood dancing takes me back to my childhood, where we would choreograph and dance to every new Bollywood beat. That brings a lot of memories and connections to childhood friends and family.

Exercise training in the management of overweight and obesity in adults: Synthesis of the evidence and recommendations from the European Association for the Study of Obesity Physical Activity Working Group

Obes Rev. 2021 Jul; 22(Suppl 4): e13273.

Exercise training in the management of overweight and obesity in adults: Synthesis of the evidence and recommendations from the European Association for the Study of Obesity Physical Activity Working Group

,

1

1,

2,3,

4,

5,

6,

6,

7,

8,

5,

4,

9,10,

9,

9,11and

9,12JeanMichel Oppert

1Assistance PubliqueHpitaux de Paris (APHP), PitiSalptrire hospital, Department of Nutrition, Institute of Cardiometabolism and Nutrition, Sorbonne University, ParisFrance

Alice Bellicha

2INSERM, Nutrition and Obesities: Systemic Approaches, NutriOmics, Sorbonne University, ParisFrance

3University ParisEst Crteil, UFR SESSSTAPS, CrteilFrance

Marleen A. van Baak

4Department of Human Biology, NUTRIM School of Nutrition and Translational Research in Metabolism, Maastricht University Medical Centre+, MaastrichtThe Netherlands

Francesca Battista

5Sport and Exercise Medicine Division, Department of Medicine, University of Padova, PadovaItaly

Kristine Beaulieu

6Appetite Control and Energy Balance Group (ACEB), School of Psychology, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Leeds, LeedsUK

John E. Blundell

6Appetite Control and Energy Balance Group (ACEB), School of Psychology, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Leeds, LeedsUK

Eliana V. Carraa

7Faculdade de Educao Fsica e Desporto, CIDEFES, Universidade Lusfona de Humanidades e Tecnologias, LisbonPortugal

Jorge Encantado

8APPsyCIApplied Psychology Research Center Capabilities and Inclusion, ISPAUniversity Institute, LisbonPortugal

Andrea Ermolao

5Sport and Exercise Medicine Division, Department of Medicine, University of Padova, PadovaItaly

Adriyan Pramono

4Department of Human Biology, NUTRIM School of Nutrition and Translational Research in Metabolism, Maastricht University Medical Centre+, MaastrichtThe Netherlands

Nathalie FarpourLambert

9Obesity Management Task Force (OMTF), European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO), MiddlesexUK

10Obesity Prevention and Care Program Contrepoids; Service of Endocrinology, Diabetology, Nutrition and Patient Education, Department of Internal Medicine, University Hospitals of Geneva and University of Geneva, GenevaSwitzerland

Euan Woodward

9Obesity Management Task Force (OMTF), European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO), MiddlesexUK

Dror Dicker

9Obesity Management Task Force (OMTF), European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO), MiddlesexUK

11Department of Internal Medicine D, Hasharon Hospital, Rabin Medical Center, Sackler School of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Tel AvivIsrael

Luca Busetto

9Obesity Management Task Force (OMTF), European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO), MiddlesexUK

12Department of Medicine, University of Padova, PadovaItaly

1Assistance PubliqueHpitaux de Paris (APHP), PitiSalptrire hospital, Department of Nutrition, Institute of Cardiometabolism and Nutrition, Sorbonne University, ParisFrance

2INSERM, Nutrition and Obesities: Systemic Approaches, NutriOmics, Sorbonne University, ParisFrance

3University ParisEst Crteil, UFR SESSSTAPS, CrteilFrance

4Department of Human Biology, NUTRIM School of Nutrition and Translational Research in Metabolism, Maastricht University Medical Centre+, MaastrichtThe Netherlands

5Sport and Exercise Medicine Division, Department of Medicine, University of Padova, PadovaItaly

6Appetite Control and Energy Balance Group (ACEB), School of Psychology, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Leeds, LeedsUK

7Faculdade de Educao Fsica e Desporto, CIDEFES, Universidade Lusfona de Humanidades e Tecnologias, LisbonPortugal

8APPsyCIApplied Psychology Research Center Capabilities and Inclusion, ISPAUniversity Institute, LisbonPortugal

9Obesity Management Task Force (OMTF), European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO), MiddlesexUK

10Obesity Prevention and Care Program Contrepoids; Service of Endocrinology, Diabetology, Nutrition and Patient Education, Department of Internal Medicine, University Hospitals of Geneva and University of Geneva, GenevaSwitzerland

11Department of Internal Medicine D, Hasharon Hospital, Rabin Medical Center, Sackler School of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Tel AvivIsrael

12Department of Medicine, University of Padova, PadovaItaly

Corresponding author.

*CorrespondenceJeanMichel Oppert, Service de Nutrition, Hpital PitiSalptrire, 4783 Boulevard de l'Hpital, 75013 Paris, France.

Email:

[email protected]Received 2021 Jan 29; Revised 2021 Apr 20; Accepted 2021 Apr 20.

Copyright2021 The Authors.

Obesity Reviewspublished by John Wiley & Sons Ltd on behalf of World Obesity Federation.

This is an open access article under the terms of the

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- Supplementary Materials

- Table S1.

Rating the strength of the evidence

1Table S2. Rating the strength of the recommendations1

GUID:E27A4EDF-61D5-489C-92D3-C066BEBCC39C

Summary

There is a need for updated practice recommendations on exercise in the management of overweight and obesity in adults. We summarize the evidence provided by a series of seven systematic literature reviews performed by a group of experts from across Europe. The following recommendations with highest strength (Grade A) were derived. For loss in body weight, total fat, visceral fat, intrahepatic fat, and for improvement in blood pressure, an exercise training program based on aerobic exercise at moderate intensity is preferentially advised. Expected weight loss is however on average not more than 2 to 3kg. For preservation of lean mass during weight loss, an exercise training program based on resistance training at moderatetohigh intensity is advised. For improvement in insulin sensitivity and for increasing cardiorespiratory fitness, any type of exercise training (aerobic, resistance, and combined aerobic or resistance) or highintensity interval training (after thorough assessment of cardiovascular risk and under supervision) can be advised. For increasing muscular fitness, an exercise training program based preferentially on resistance training alone or combined with aerobic training is advised. Other recommendations deal with the beneficial effects of exercise training programs on energy intake and appetite control, bariatric surgery outcomes, and quality of life and psychological outcomes in management of overweight and obesity.

Keywords: exercise, obesity, physical activity, recommendations

1.INTRODUCTION

Physical activity is recognized as a pillar in the management of overweight and obesity, in parallel with dietary counseling, behavioral support, medication, and, in some instances, bariatric surgery.1 Physical activity is defined in broad terms as any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that results in energy expenditure.2 Exercise is viewed as a subcategory of physical activity that is planned, structured, repeated with a given purpose, to maintain or increase physical fitness (see Glossary, Table).2 Although the value of physical activity and exercise for maintaining health and preventing noncommunicable diseases is acknowledged as a public health best buy,3, 4 the role they may have for weight control remains debated both in the scientific5 and lay literature.6

TABLE 1

Glossary of terms (adapted from WHO Guidelines3 and PAGAC4)

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Physical activity | Any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that requires energy expenditure |

| Exercise training | Exercise is a subcategory of physical activity that is planned, structured, repetitive, and purposeful with primary purpose of improving or maintaining physical fitness, physical performance, or health. |

| Aerobic training | Programs based on forms of activities that are intense enough and performed long enough to maintain or improve an individual's cardiorespiratory fitness. Here, aerobic refers to moderateintensity aerobic training. On a scale relative to an individual's personal capacity, moderateintensity physical activity is usually a 5 or 6 on a scale of 010. Based on heart rate, moderateintensity physical activity is usually defined as 50%70% of maximal heart rate. |

| Resistance training | Also referred to as musclestrengthening activities: programs based on activities that increase skeletal muscle strength, power, endurance, and mass and that involve major muscle groups (legs, back, abdomen, chest, shoulders, and arms). Intensity of resistance training is usually defined according to the onerepetition maximum (1RM). Moderate intensity is usually defined as more than 60% of the 1RM. |

| Highintensity interval training (HIIT) | Consists of short periods of highintensity anaerobic exercise, commonly less than 1min, alternating with short periods of less intense recovery. |

| Physical fitness | A measure of the body's ability to function efficiently and effectively in dailylife activities. Includes cardiorespiratory fitness, muscle strength, balance, and flexibility. |

Several important reviews and position statements have been issued on the topic of physical activity and exercise regarding management of obesity during the 2000s.7, 8, 9 However, there has not been any systematic effort to get an overall update of more recent existing knowledge. Such overview would however be much needed to inform the design of practice guidelines for routine management of overweight and obesity in adults. In particular, there is a need for updated knowledge on the effects of various forms of exercise training programs (e.g., aerobic, resistance, or combined training) on weight loss, body composition changes with weight loss, and weight maintenance after weight loss in adults with overweight and obesity. Moreover, several topics of major importance have not been comprehensively addressed in previous reviews such as the effect of specific exercise training program in persons with overweight and obesity on intrahepatic fat, insulin sensitivity, blood pressure, cardiorespiratory and muscle fitness, eating behavior, hunger and satiety, and quality of life and psychological wellbeing. To fill these gaps, a working group of European experts was convened in 2019 under the auspices of the European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO10). EASO is a federation of professional membership associations from 36 countries across Europe and it produces guidelines as a key element of the education about obesity management.

The goals assigned to the EASO Physical Activity Working Group were to synthesize the literature on topics of importance in the field of exercise in management of overweight and obesity as published since 2010 and to write down the evidence on each of these topics in the form of systematic review papers, with metaanalyses when applicable. The working group included clinical and nonclinical obesity experts with specific expertise in the field of physical activity and exercise: physiology, health care, psychology, and behavior change techniques. The literature search addressed the overall effect of exercise training on a series of outcomes of major interest in the management of overweight or obesity: body weight and body composition changes, metabolic health, physiological outcomes (fitness), behavioral outcomes (energy intake and appetite), bariatric surgery outcomes, and psychological outcomes. Attention was also directed to specific outcomes that had not been extensively reviewed before in the population of persons with overweight or obesity, such as the effects of exercise training on visceral and intrahepatic fat, muscular fitness, energy intake and appetite, healthrelated quality of life, and the comparison between different exercise training modes.

The present paper summarizes the approach taken to synthesize recent literature on the abovementioned issues. The resulting evidence statements on the role of exercise in management of overweight and obesity are presented and discussed. This text therefore represents a summary of the material detailed in the accompanying papers on each outcome of interest. Recommendations regarding exercise in the management of overweight and obesity are presented as a final output of this work.

2.METHODS

All members of the working group followed the same methods to synthesize the evidence and format the recommendations, with variations as needed to reflect the evidence available in each field. The methodology followed a prespecified development process in three steps: (1) conducting of systematic reviews and metaanalyses (SRMAs), (2) writing of evidence statements, and (3) designing of recommendations.

2.1. Systematic reviews and metaanalyses

The systematic reviews followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and MetaAnalysis (PRISMA) guidelines and were registered in the PROSPERO database (registration number CRD42019157823). Seven a priori defined research questions (Q1 to Q7) were addressed in the systematic reviews included in this supplement (Table). The details of methods used for each outcome under study are to be found in the corresponding papers of the series.

TABLE 2

List of research questions

| Q1 | Effect of exercise training interventions on weight loss, body composition changes and weight maintenance11 |

| Q2 | Effect of exercise training interventions on cardiometabolic health12 |

| Q3 | Effect of exercise training interventions on physical fitness13 |

| Q4 | Effect of exercise training interventions on energy intake and appetite14 |

| Q5 | Effect of exercise training interventions in the context of bariatric surgery15 |

| Q6 | Effect of exercise training interventions on quality of life and psychological outcomes16 |

| Q7 | Behavior change techniques to increase physical activity17 |

Briefly, depending on the topic, three to four electronic databases were searched (PubMed, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, PsychInfo, and SportDiscus) for original studies (Q2 to Q7) published up to 2020. The article addressing the first research question (Q1: effect of exercise on weight loss, body composition changes, and weight maintenance) was an overview of reviews, and the search was therefore limited to SRMAs. To avoid overlaps between SRMAs, we included only SRMAs published from January 2010 to December 2019.

Generic terms related to obesity and physical activity were used. Limits were set to include reviews/articles published in English. Reference lists from the resulting reviews and articles were also screened to identify additional articles. Articles were included if they involved adults (18years including older adults) with overweight (body mass index, BMI25kg/m2) or obesity (BMI30kg/m2) as defined for Caucasian populations18 participating in an exercise training program. Presence of obesity comorbidities was not an exclusion criterion; for example, an article on subjects with obesity and type 2 diabetes was not excluded, whereas an article focused on subjects with type 2 diabetes (who usually have overweight or obesity, but this was not specified as an inclusion criterion) was excluded. Specifically, subjects with the following comorbidities were not excluded: type 2 diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, metabolic syndrome, liver disease (NAFLD/NASH), and osteoarthritis. Those with the following comorbidities were excluded: cardiovascular disease (coronary artery disease, stroke, and heart failure), cancers, rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, kidney failure, neuropathy, severe orthopedic disorders (with important mobility limitations), intellectual deficiency, psychiatric conditions, fibromyalgia, asthma, and sleep disorders.

No minimum intervention length criterion was applied. Exercise training programs included sessions with one or more types of exercise (aerobic and/or resistance and/or highintensity interval training, HIIT). Exercise sessions could be fully supervised, partially supervised, or nonsupervised. Four systematic reviews (Q1, Q2, Q3, and Q5) included only randomized or nonrandomized controlled trials and three systematic reviews (Q4, Q6, and Q7) also included singlegroup interventions. One review (Q1) that was an overview of reviews included only SRMAs of controlled trials. Exercise interventions in combination with other interventions (e.g., diet) with appropriate controls were included, except for Q3 that focused on exerciseonly interventions. Comparators included no intervention or usual care (i.e., intervention that any patient would have received in the framework of obesity management) or dietary interventions without exercise training or drug treatment.

Data were extracted using standardized forms. The effects of exercise were assessed using randomeffects metaanalyses (Cochrane Review Manager 5.3 or Comprehensive MetaAnalysis version 3). Effect sizes were reported as mean difference, MD, or standardized mean difference, SMD, alongside their 95% confidence intervals (CI) and p values and were categorized as large, medium, small, or negligible. A p value<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

To assess study quality (good, fair, or poor), we used the tool developed by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI, USA) that has been previously used for defining guidelines for the management of obesity.19 The original assessment forms for SRMAs, controlled trials, crossover trials, and singlegroup interventions were used. Publication bias was assessed by visual inspection of the funnel plots and when the number of included studies was >10, Egger's test and sometimes additional tests were performed (see individual papers for more details).

2.2. Evidence statements

Four to seven evidence statements were defined for each research question. The strength of each evidence statement was rated as high, moderate or low (TableS1) using the tool developed by the NHLBI.19 The strength of evidence represents the degree of certainty, based on the overall body of evidence, that an effect or association is correct.19

2.3. Recommendations

Recommendations were mainly formatted based on evidence statements with moderate to high strength of evidence. Members of the working group graded the recommendations as Strong Recommendation (Grade A), Moderate Recommendation (Grade B), Weak Recommendation (Grade C), Recommendation Against (Grade D), Expert Opinion (Grade E), or No Recommendation for or Against (Grade N) (TableS2).

3.RECOMMENDATIONS

A total of 15 recommendations are proposed regarding exercise training for (1) weight and fat loss, (2) weight maintenance after weight loss, (3) preservation of lean body mass during weight loss, (4) visceral fat loss and intrahepatic fat loss, (5) insulin sensitivity, (6) blood pressure, (7) cardiorespiratory fitness, (8) muscular fitness, (9) eating behavior, (10) hunger and satiety, (11) quality of life (physical component), (12) additional weight and fat loss with exercise after bariatric surgery, (13) physical fitness after bariatric surgery, (14) preservation of lean body mass after bariatric surgery, and (15) behavior change techniques for promoting physical activity (Table).

TABLE 3

Summary of recommendations

| Recommendation | Grade | Corresponding ESs |

|---|---|---|

| Body weight and body composition | ||

| 1. Weight and fat loss | ||

| Advise preferentially an exercise training program based on 150 to 200min of aerobic exercise at least at moderate intensity. | A | 1.11.21.4 |

| Advise an exercise training program based on HIIT (i) only after thorough assessment of cardiovascular risk and (ii) with supervision. | B | 1.3 |

| Inform persons with overweight or obesity that expected weight loss is on average not more than 2 to 3kg. | A | 1.11.4 |

| 2. Weight maintenance after weight loss | ||

| Advise a high volume of aerobic exercise (200 to 300min/week of moderateintensity exercise). | E | 1.7 |

| 3. Preservation of lean body mass during weight loss | ||

| Advise an exercise training program based on resistance training at moderatetohigh intensity. | A | 1.6 |

| Cardiometabolic health | ||

| 4. Visceral fat loss and intrahepatic fat loss | ||

| Advise preferentially an exercise training program based on aerobic exercise at moderate intensity. | A | 1.52.4 |

| Advise an exercise training program based on HIIT (i) only after thorough assessment of cardiovascular risk and (ii) with supervision. | B | 1.52.4 |

| 5. Insulin sensitivity | ||

| Advise any type of exercise training (aerobic, resistance, and combined aerobic or resistance) or HIIT (after thorough assessment of cardiovascular risk and under supervision). | A | 2.1 |

| 6. Blood pressure | ||

| Advise preferentially an exercise training program based on aerobic exercise at moderate intensity. | A | 2.22.3 |

| Physical fitness | ||

| 7. Cardiorespiratory fitness | ||

| Advise any type of exercise training (aerobic, resistance, and combined aerobic or resistance) or HIIT (after thorough assessment of cardiovascular risk and under supervision). | A | 3.13.2 |

| 8. Muscular fitness | ||

| Advise an exercise training program based preferentially on resistance training alone or combined with aerobic training. | A | 3.33.4 |

| Energy intake and appetite | ||

| 9. Eating behavior | ||

| Inform persons with overweight or obesity that an exercise training program will not have a substantial impact on energy intake but rather may improve eating behaviors. | B | 4.14.4 |

| 10. Hunger and satiety | ||

| Inform persons with overweight or obesity that exercise training may increase fasting hunger but improve the strength of satiety | B | 4.24.3 |

| Quality of life and psychological wellbeing | ||

| 11. Quality of life (physical component) | ||

| Advise an exercise training program based on either aerobic, resistance or a combination of both. | B | 6.1 |

| Bariatric surgery | ||

| 12. Additional weight and fat loss with exercise after surgery | ||

| Advise an exercise training program based on a combination of aerobic and resistance training. | A | 5.1 |

| Inform that expected additional weight and fat loss is on average not more than 2 to 3kg. | B | 5.1 |

| 13. Physical fitness | ||

| Advise an exercise training program based on a combination of aerobic and resistance training. | A | 5.2 |

| 14. Lean body mass | ||

| Advise an exercise training program based on a combination of aerobic and resistance training. | C | 5.3 |

| Behavior change techniques | ||

| 15. Habitual physical activity | ||

| Preferentially use prompting behavioral practice and rehearsal in facetoface behavior change interventions. | B | 7.4 |

4.RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND CORRESPONDING EVIDENCE STATEMENTS

4.1. Q1Weight loss, body composition changes, and weight maintenance

4.1.1. Statement of the question

In adults with overweight or obesity

1aWhat is the effect of exercise training programs on weight loss, changes in body composition (fat mass, visceral adipose tissue, and lean body mass), and weight maintenance?

1bWhat are the effects of different types of exercise training (aerobic, resistance, aerobic and resistance combined, and HIIT) on these parameters?

4.1.2. Search

Q1 was restricted to SRMAs published between 2010 and December 2019. The titles and abstracts of 3320 articles were screened against the inclusion and exclusion criteria, which resulted in 2337 articles being excluded and 123 being retrieved for fulltext review to further assess eligibility. Of the 123 articles, 12 SRMAs met the criteria and were included. A total of 149 unique original articles were included in the metaanalyses. Three (25%) SRMAs were rated as good quality, 8 (67%) as fair quality, and 1 (8%) as poor quality. The most recent SRMA that focused on weight maintenance was published in 2014 (Johansson et al.20) and included only three original studies. Therefore, an additional search for original controlled trials on this outcome published between 2010 and July 2020 was performed. From 2422 articles identified and 13 articles retrieved for fulltext review, one controlled trial of fair quality was included.

4.1.3. Evidence statements

Evidence statement 1.1: Aerobic training reduces body weight (by approximately 2 to 3kg on average compared to controls without training and without dietary intervention and by 1kg compared to resistance training alone) in groups of adults with overweight or obesity, independent of the duration of intervention.

Evidence statement 1.5: Aerobic training and HIIT, but not resistance training, reduce abdominal visceral fat as measured by CT or MRIscanning techniques in groups of adults with overweight or obesity, compared to controls without training.

Evidence statement 1.6: Resistance training, but not aerobic training, performed during a weightloss diet decreases the loss of lean body mass in groups of adults with overweight or obesity, compared to controls with diet only.

4.2. Q2Cardiometabolic health

4.2.1. Statement of the question

In adults with overweight or obesity

2aWhat is the effect of exercise training programs on insulin sensitivity, blood pressure, and intrahepatic fat?

2bWhat are the effects of different types of exercise training (aerobic, resistance, aerobic and resistance combined, and HIIT) on these parameters?

4.2.2. Search

The literature search for Q2 was limited to controlled trials published up to April 2020. Of the 6768 articles initially screened, 242 fulltext articles were assessed for eligibility and 54 met the inclusion/exclusion criteria and were included. The effect of exercise on insulin sensitivity, blood pressure, and intrahepatic fat was assessed in 36, 30, and 13 studies, respectively. In addition, the effect of exercise on insulin sensitivity and blood pressure was assessed according to the status of participants (with or without type 2 diabetes, with or without hypertension, respectively). Study quality was rated as good, fair, and poor in 11 (20%), 20 (37%), and 23 (43%) studies, respectively.

4.2.3. Evidence statements

Evidence statement 2.2: Exercise training programs (aerobic, resistance, or HIIT) reduce systolic blood pressure by approximately 3mmHg on average in groups of adults with overweight or obesity and with hypertension compared to controls without training.

Evidence statement 2.3: Exercise training programs (aerobic, resistance, or HIIT) reduce diastolic blood pressure by approximately 2mmHg on average in groups of adults with overweight or obesity with or without hypertension compared to controls without training.

4.3. Q3Physical fitness

4.3.1. Statement of the question

In adults with overweight or obesity

3aWhat is the effect of exercise training programs on cardiorespiratory fitness and muscle strength?

3bWhat are the effects of different types of exercise training (aerobic, resistance, aerobic and resistance combined, HIIT) on these parameters?

4.3.2. Search

A systematic search of RCTs published up to December 2019 was performed. Of the 3068 articles initially screened, 162 fulltext articles were assessed for eligibility and 82 met the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Of these, 66 were included in the metaanalyses. In these studies, comparisons were made either between an exercise group and a nonexercise group, or between different types of exercise training. Study quality was rated as good, fair, and poor in 21 (32%), 28 (42%), and 17 (26%) studies, respectively.

4.3.3. Evidence statements

Evidence statement 3.1: Aerobic, resistance, combined aerobic plus resistance, and HIIT interventions all increase VO2max compared with no exercise training in groups of adults with overweight or obesity.

4.4. Q4Energy intake and appetite control

4.4.1. Statement of the question

In adults with overweight or obesity

4aWhat is the effect of exercise training programs on energy intake and appetite control (appetite ratings, eating behavior traits, and food reward)?

4bWhat are the effects of different types of exercise training (aerobic, resistance, aerobic and resistance combined, and HIIT) on these parameters?

4.4.2. Search

A systematic search of controlled trials, crossover trials, and singlegroup interventions published up to October 2019 was performed. Only exercise training interventions were included as the combination with other interventions (e.g., diet and cognitive behavioral therapy) may influence energy intake and/or appetite control. Additionally, only exercise training interventions where diet was free to vary were included in the energy intake analysis. Comparators included noexercise controls. Of the 4593 articles initially screened, 155 fulltext articles were assessed for eligibility and 48 met the inclusion/exclusion criteria and were included. Study quality was rated as good, fair, and poor in 2 (4%), 7 (15%), and 39 (81%) studies, respectively.

4.4.3. Evidence statements

4.5. Q5Bariatric surgery

4.5.1. Statement of the question

In adults with severe obesity undergoing bariatric surgery

5aWhat is the effect of preoperative exercise training programs on weight loss, changes in body composition, physical fitness, cardiometabolic health, habitual physical activity, and healthrelated quality of life?

5bWhat is the effect of postoperative exercise training programs on weight loss, changes in body composition, physical fitness, cardiometabolic health, habitual physical activity, and healthrelated quality of life?

4.5.2. Search

Q5 was restricted to controlled trials published up to October 2019. Of the 2858 articles initially screened, 65 fulltext articles were assessed for eligibility and 31 met the inclusion/exclusion criteria and were included. A total of 22 distinct exercise training programs were analyzed, of which 18 programs were performed after bariatric surgery and 4 before surgery. The comparator was a group of adults undergoing bariatric surgery without exercise training. Study quality was rated as good, fair, and poor in 9 (43%), 4 (19%), and 8 (38%) studies.

4.5.3. Evidence statements

Evidence statement 5.2: Exercise training (aerobic, resistance, or a combination of both) conducted after bariatric surgery improves cardiorespiratory fitness (VO2max, walking distance) and muscle strength.

Evidence statement 5.3: Exercise training (aerobic, resistance, or a combination of both) conducted after bariatric surgery reduces the loss of lean body mass occurring during the first year after bariatric surgery, compared to controls without exercise after surgery.

4.6. Q6Psychological outcomes and quality of life

4.6.1. Statement of the question

In adults with overweight or obesity

6aWhat is the effect of exercise training programs on quality of life, depression, anxiety, perceived stress, body image, and other psychological outcomes?

6bWhat are the effects of different types of exercise training (aerobic, resistance, aerobic and resistance combined, and HIIT) on these parameters?

4.6.2. Search

A systematic search of controlled trials and singlegroup interventions published up to October 2019 was performed. Of the 1298 articles initially screened, 74 fulltext articles were assessed for eligibility and 36 met the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Twentyone studies were included in metaanalysis. Most studies (32 out of 36) were RCTs. Study quality was rated as good, fair, and poor in 14 (39%), 14 (39%), and 8 (22%) studies, respectively. Supervised or semisupervised exercise interventions, assessing one or more psychosocial outcomes (both pre and postexercise or compared with control), were included. Studies involving multicomponent interventions (e.g., exercise paired with a behavioral intervention or diet) were excluded if the isolated effect of exercise could not be determined (e.g., diet+exercise vs. control and behavioral intervention vs. control).

4.6.3. Evidence statements

Evidence statement 6.5: Combined aerobic plus resistance exercise training programs appear to induce greater improvements in quality of life, compared to aerobiconly or resistanceonly training programs, in adults with overweight or obesity.

4.7. Q7Behavior change techniques

4.7.1. Statement of the question

In adults with overweight or obesity

7aWhat are the most effective behavior change techniques for increasing physical activity in facetoface interventions?

7bWhat are the most effective behavior change techniques for increasing physical activity in digital interventions?

4.7.2. Search

The search for Q7 was restricted to RCTs published up to October 2019. Of the 1760 articles initially screened, 168 fulltext articles were assessed for eligibility and 53 met the inclusion/exclusion criteria and were included. From these, 35 studies referred to digital trials and 28 studies to facetoface trials. Study quality was rated as good, fair, and poor in 15 (24%), 26 (42%), and 21 (34%) studies, respectively. No previous systematic review and metaanalysis have examined the effectiveness of motivational behavior change techniques21 along with the behavior change technique taxonomy (BCTTv1),22 or separately analyzed behavior change techniques effectiveness in changing physical activity in digital and faceto face interventions in adults with overweight or obesity. Behavior change interventions that primarily or secondarily aimed at increasing physical activity were included. Comparators included no intervention, standard care, or dietary intervention without a physical activity practice or counseling component.

4.7.3. Evidence statements

Evidence statement 7.2: Digital behavior change interventions using goal setting, social incentive and graded tasks might result in greater increases in physical activity than interventions that do not use these behavior change techniques, in groups of adults with overweight or obesity.

Evidence statement 7.4: Facetoface behavior change interventions (taking place physically, on site) prompting behavioral practice and rehearsal might lead to more favorable physical activity outcomes, compared to facetoface interventions that do not use this behavior change technique, in groups of adults with overweight or obesity.

5.GAPS IN EVIDENCE AND PRIORITY RESEARCH NEEDS

In general, findings of the series of reviews performed show gaps in current knowledge in a number of aspects:

Interindividual variability in response to exercise and its consequences for management of persons with overweight or obesity needs further exploration.

Better understanding of the importance of exercise, and different types and timing of exercise, on appetite control and eating behavior would greatly improve management strategies.

The value of physical activity counseling versus structured exercise training should be better defined.

Effects of HIIT were found of interest on several outcomes; however, feasibility and acceptability in reallife settings would need further delineation in persons with overweight or obesity.

More specific questions include defining the volume of physical activity required for weight maintenance after weight loss, including after bariatric surgery.

Optimal timing of exercise training interventions after bariatric surgery would require investigation.

Assessing whether the effects of aerobic and strength training in persons with overweight or obesity are of about the same magnitude as in lean subjects would help better tailor prescriptions.

More evidence would be needed on psychological outcomes (such as body image, anxiety, perceived stress, and life satisfaction) as well as on effects of individual versus groupbased exercise training.

Which combination of behavior change techniques (facetoface or digital) are most effective for increasing physical activity and how they should be administered remains an open question.

Improved knowledge of doseresponse relationships between volume of exercise and effects on given outcomes would be needed to design quantitative guidelines specific to persons with overweight or obesity.

The importance of reducing sedentary behavior (e.g., sitting time) should be assessed in management of overweight and obesity.

Capacity building of instructors and coaches in offering exercise programs adapted to the needs and capabilities of persons with obesity should be developed.

Finally, how to increase adherence to prescribed exercise, especially in the long term, should be explored in depth. The value of wearable devices and apps for this purpose needs to be examined in subjects with overweight or obesity.

6.IMPLICATIONS FOR CLINICAL PRACTICE

Based on the evidence gathered through our systematic search and analysis of the literature on exercise in the management of overweight and obesity in adults, some implications for practice can be proposed. It is important to emphasize the numerous health benefits to be gained with higher physical activity and fitness levels in persons with overweight or obesity. Given that effects on weight (and fat) loss as such were found of modest size, the implementation of exercise training programs in persons with overweight or obesity should primarily aim to increase physical fitness, reduce cardiometabolic risk, and improve quality of life. These benefits of exercise will very likely improve overall health, even without substantial change in body weight.

Within the scope of a comprehensive approach of management of overweight and obesity, exercise prescription will be carried out in conjunction with dietary advice, psychological interventions, pharmacotherapy when needed and/or available, and in persons with severe obesity, bariatric surgery.19, 23 The five A's strategy consisting Ask, Assess, Advise, Agree, and Assist (or Arrange)24, 25 appears well adapted in this perspective, especially for the aim to individually tailor the exercise prescription to the needs, preferences, capacity, corpulence, and health status of patients.

The topic of physical activity and exercise should be discussed as part of each encounter between a health professional and any patient with overweight or obesity (Ask). Information about the benefits expected should be provided. An evaluation of habitual physical activity and physical fitness is a logical followup of dietary and lifestyle assessment in patients (Assess). Simple questionnaires designed for use in the setting of general practice can help.26 There is currently no specific recommendation about when to perform a maximal exercise test in subjects with overweight or obesity (without diabetes). Such testing may however be important to search for underlying coronary heart disease in highrisk patients and/or to adapt the exercise load on a quantitative basis.27 A specific goal should be defined for the patient and specific activities or programs proposed to reach that goal (Advise). Goals will be shared between health professionals and patients (Agree). Counseling will be tailored to the individual needs of the patients taking into account physical fitness, comorbidities, stage of change regarding physical activity, barriers to increase physical activity, and opportunities offered in the living environment. The process of counseling will develop over time with frequent reassessment and subsequent adaptation (Assist). Interventions rest on behavior change and a major challenge is how to improve adherence to a new lifestyle over time.28

When recommending exercise for adults with overweight or obesity, it is important to balance any positive with potential negative effects on health. In the general population, exercise is associated with an increased risk of musculoskeletal injuries and adverse cardiac events, but there is evidence from nonrandomized trials and observational studies that the benefits of exercise far outweigh the risks in most adults.29 Musculoskeletal injuries are the most frequent negative side effects of exercise. There is however very little information on musculoskeletal injuries in adults with overweight or obesity during exercise interventions. Some studies in this setting did not find more injuries in the intervention group than in the control group,30, 31 while other studies reported more injuries in an exercise intervention group.32, 33 We are not aware of studies that directly compared the injury risk in adults with or without overweight or obesity. The incidence of both acute myocardial infarction and sudden death is greatest in the least habitually physically active individuals performing unaccustomed physical activity.34 It is likely that a larger percentage of adults with overweight or obesity falls in this inactive group compared to lean subjects. On the other hand, the largest benefits on allcause mortality are attained when this group is moved to an at least moderately active level.35 By analogy with the general population, overall it seems prudent to advise habitually inactive adults with obesity to become more active by a gradual progression of exercise volume by adjusting exercise duration, frequency, and/or intensity.29

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No conflict of interest statement.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors participated to the writing of evidence statements and recommendations. JMO and AB drafted the manuscript, and authors critically revised the manuscript.

Supporting information

Table S1. Rating the strength of the evidence1

Table S2. Rating the strength of the recommendations1

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to thank the European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO) for support in conducting this work.

Notes

Oppert JM, Bellicha A, van Baak MA, et al. Exercise training in the management of overweight and obesity in adults: Synthesis of the evidence and recommendations from the European Association for the Study of Obesity Physical Activity Working Group. Obesity Reviews. 2021;22(S4):e13273. 10.1111/obr.13273 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

PROSPERO registration number: CRD42019157823.

REFERENCES

1.

Bray GA, Frhbeck G, Ryan DH, Wilding JPH. Management of obesity. The Lancet. 2016;387(10031):19471956. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00271-3 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]2.

Caspersen CJ, Powell KE, Christenson GM. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for healthrelated research. Public Health Rep. 1985;100(2):126131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]3.

WHO. WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. [Google Scholar]4.

PAGAC. Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Report. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2018. [Google Scholar]5.

Washburn RA, Szabo AN, Lambourne K, et al. Does the method of weight loss effect longterm changes in weight, body composition or chronic disease risk factors in overweight or obese adults? A systematic review. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e109849. 10.1371/journal.pone.0109849 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]7.

Donnelly JE, Blair SN, Jakicic JM, et al. American College of Sports Medicine Position Stand. Appropriate physical activity intervention strategies for weight loss and prevention of weight regain for adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(2):459471. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181949333 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]8.

Saris WH, Blair SN, van Baak MA, et al. How much physical activity is enough to prevent unhealthy weight gain? Outcome of the IASO 1st Stock Conference and consensus statement. Obes Rev. 2003;4(2):101114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]9.

Fogelholm M, Stallknecht B, Baak MV. ECSS position statement: exercise and obesity. Eur J Sport Sci. 2006;6(1):1524. 10.1080/17461390600563085 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]11.

Bellicha A, van Baak MA, Battista F, Beaulieu K, Blundell JE, Busetto L, et al. Effect of exercise training on weight loss, body composition changes, and weight maintenance in adults with overweight or obesity: An overview of 12 systematic reviews and 149 studies. Obes Rev. 2021;22(Suppl 4):e13256. 10.1111/obr.13256 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]12.

Battista F, Ermolao A, van Baak MA, Beaulieu K, Blundell JE, Busetto L, et al. Effect of exercise on cardiometabolic health of adults with overweight or obesity: Focus on blood pressure, insulin resistance, and intrahepatic fatA systematic review and metaanalysis. Obes Rev. 2021;22(Suppl 4):e13269. 10.1111/obr.13269 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]13.

Van Baak M, Pramono A, Battista F, Beaulieu K, Blundell JE, Busetto L, et al. Effect of different types of regular exercise on physical fitness in adults with overweight or obesity: systematic review and metaanalyses. Obes Rev. 2021;22(Suppl 4):e13239. 10.1111/obr.13239 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]14.

Beaulieu K, Blundell JE, van Baak MA, Battista F, Busetto L, Carraa EV, et al. Effect of exercise training interventions on energy intake and appetite control in adults with overweight or obesity: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Obes Rev. 2021;22(Suppl 4):e13251. 10.1111/obr.13251 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]15.

Bellicha A, van Baak MA, Battista F, Beaulieu K, Blundell JE, Busetto L, et al. Effect of exercise training before and after bariatric surgery: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Obes Rev. 2021;22(Suppl 4):e13296. 10.1111/obr.13296 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]16.

Carraa EV, Encantado J, van Baak MA, Battista F, Beaulieu K, Blundell JE, et al. Effect of Exercise Training on Psychological Outcomes in Adults with Overweight or Obesity: A Systematic Review and MetaAnalysis. Obes Rev. 2021;22(Suppl 4):e13261. 10.1111/obr.13261 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]17.

Carraa E, Encantado J, Battista F, Beaulieu K, Blundell J, Busetto L, et al. Effective behavior change techniques to promote physical activity in adults with overweight or obesity: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Obes Rev. 2021;22(Suppl 4):e13258. 10.1111/obr.13258 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]19.

Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation. 2014;129(25 Suppl 2):S102S138. 10.1161/01.cir.0000437739.71477.ee [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]20.

Johansson K, Neovius M, Hemmingsson E. Effects of antiobesity drugs, diet, and exercise on weightloss maintenance after a verylowcalorie diet or lowcalorie diet: a systematic review and metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(1):1423. 10.3945/ajcn.113.070052 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]21.

Teixeira PJ, Marques MM, Silva MN, et al. A classification of motivation and behavior change techniques used in selfdetermination theorybased interventions in health contexts. Motiv Sci. 2020;6(4):438455. 10.1037/mot0000172 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]22.

Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med Publ Soc Behav Med. 2013;46(1):8195. 10.1007/s12160-013-9486-6 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]24.

Sturgiss E, van Weel C. The 5 As framework for obesity management: do we need a more intricate model? Can Fam Physician Med Fam Can. 2017;63(7):506508. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]26.

Ahmad S, Harris T, Limb E, et al. Evaluation of reliability and validity of the General Practice Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPPAQ) in 6074year old primary care patients. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16(1):113. 10.1186/s12875-015-0324-8 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]27.

Fletcher GF, Ades PA, Kligfield P, et al. Exercise standards for testing and training: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;128(8):873934. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829b5b44 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]28.

Burgess E, Hassmn P, Pumpa KL. Determinants of adherence to lifestyle intervention in adults with obesity: a systematic review. Clin Obes. 2017;7(3):123135. 10.1111/cob.12183 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]29.

Garber CE, Blissmer B, Deschenes MR, et al. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(7):13341359. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318213fefb [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]30.

Janney CA, Jakicic JM. The influence of exercise and BMI on injuries and illnesses in overweight and obese individuals: a randomized control trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;7(1):1. 10.1186/1479-5868-7-1 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]31.

Fealy CE, Nieuwoudt S, Foucher JA, et al. Functional highintensity exercise training ameliorates insulin resistance and cardiometabolic risk factors in type 2 diabetes. Exp Physiol. 2018;103(7):985994. 10.1113/EP086844 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]32.

Jeffery RW, Wing RR, Sherwood NE, Tate DF. Physical activity and weight loss: does prescribing higher physical activity goals improve outcome? Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78(4):684689. 10.1093/ajcn/78.4.684 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]33.

Campbell K, FosterSchubert K, Xiao L, et al. Injuries in sedentary individuals enrolled in a 12month, randomized, controlled, exercise trial. J Phys Act Health. 2012;9(2):198207. 10.1123/jpah.9.2.198 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]34.

Thompson PD, Franklin BA, Balady GJ, et al. Exercise and acute cardiovascular events placing the risks into perspective: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism and the Council on Clinical Cardiology. Circulation. 2007;115(17):23582368. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.181485 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]35.

Bauman AE. Updating the evidence that physical activity is good for health: an epidemiological review 20002003. J Sci Med Sport. 2004;7(1 Suppl):619. 10.1016/s1440-2440(04)80273-1 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]